Tracking post-translational modifications (PTMs) as they occur inside living cells has long been one of biology’s most persistent analytical challenges. Most methods rely on breaking open cells, collecting extracts, or performing endpoint assays — approaches that obscure the rapid, dynamic nature of protein regulation. Now, researchers at Rice University have engineered a “living sensor” system that allows cells to biosynthesize and incorporate a 21st amino acid into proteins, creating bioluminescent reporters that glow when PTMs are removed.

The platform works in bacteria, mammalian cells, and even live tumor models, giving scientists an unprecedented real-time view of enzymatic activity inside intact biological systems. In one demonstration, the team monitored the cancer-linked deacetylase SIRT1 during tumor development and found that inhibiting the enzyme blocked its molecular activity but did not slow tumor growth — challenging widely held assumptions about its role in cancer.

To learn more about this work and what living sensors could mean for the future of PTM research, drug discovery, and personalized medicine, we spoke with Han Xiao, Professor of Chemistry, Bioengineering, Biosciences at Rice University, USA, and corresponding author of the study.

What inspired the idea of creating a “living sensor” system?

The concept of a “living sensor” arose from our long-standing interest in developing tools that can directly monitor molecular events inside living systems, rather than relying on snapshots from cell extracts or tissue samples. In analytical chemistry, most measurements are taken after a biological process has already occurred. We wanted to break that limitation by designing a system that could perform continuous, in situ monitoring within cells and even animals.

How does it work?

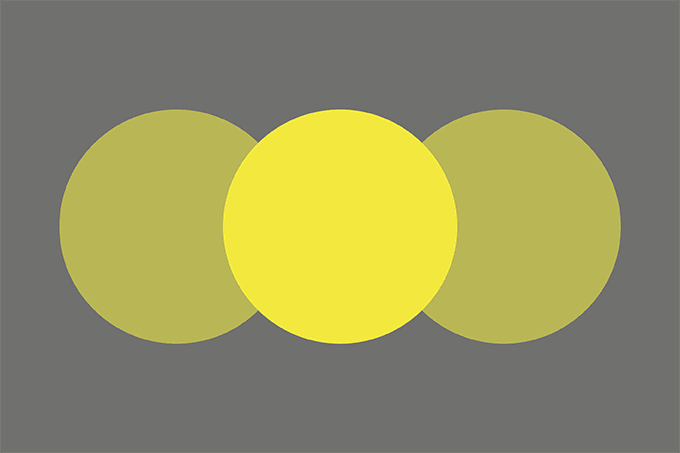

We introduce an enzyme called RDW23166.1 into cells to make a 21st amino acid, acetyllysine. By genetic code expansion technology, we enabled cells to insert this modified amino acid into proteins during biosynthesis. When built into a luciferase reporter, acetyllysine blocks light emission — but when enzymes like SIRT1 remove the acetyl group, the light returns. This lets us directly visualize post-translational modifications inside living systems.

What new analytical advantages does it offer?

Conventional assays detect protein modifications after cell lysis, offering only endpoint or bulk measurements. Our system instead performs in situ sensing — the cell itself becomes the analytical device. By encoding acetyllysine directly into proteins, we can monitor enzymatic activity continuously and quantitatively through a bioluminescent readout. This provides high temporal resolution, real-time kinetics, and single-cell level insight into post-translational modifications that traditional methods cannot achieve.

Did any of the results surprise you?

One of the most surprising findings came from monitoring SIRT1 activity during tumor development. SIRT1, a key deacetylase regulating metabolism, DNA repair, and cancer progression, has been difficult to track in living systems. Using our living SIRT1 cell sensor, we observed that a highly specific and potent SIRT1 inhibitor (EX-527) effectively blocked SIRT1 activity but did not slow HCT116 tumor growth. This suggests that, while SIRT1 inhibition works at the molecular level, its impact on tumor progression depends on cell type and other biological factors, and may not be generalizable across all cancers. These results reveal that acetylation signaling is far more dynamic and context-dependent than previously assumed, challenging static models of SIRT1 function in tumorigenesis.

What were the main technical hurdles that had to be overcome?

While our autonomous cell-based sensor system reliably monitors SIRT1 activity in vivo, several technical challenges had to be addressed. The cells needed to autonomously produce sufficient amounts of the 21st amino acid for reliable protein incorporation, reporters had to be highly sensitive and specific to enzyme activity, and the system had to remain stable in complex tumor environments. Factors such as hypoxia, tissue heterogeneity, fluctuating nutrient availability, and variable drug penetration can all influence sensor performance and signal output. By overcoming these hurdles, we achieved accurate, real-time monitoring of post-translational modifications in living systems. Future studies will systematically assess these variables to optimize the sensor for diverse physiological and pathological conditions.

Finally, what’s next for this technology?

The platform is highly adaptable — by engineering cells to biosynthesize other noncanonical amino acids, we could create living sensors for modifications like methylation or phosphorylation. This opens up opportunities for real-time monitoring of diverse enzymatic activities in living cells or animal models. Beyond basic research, such sensors could be used in drug discovery, to screen inhibitors more efficiently, or even in personalized medicine, to track patient-specific responses to therapies in real time.