Subtle chemical differences in colonial iron artifacts may help archaeologists distinguish between centuries – and even between overlapping Spanish expeditions – according to a new study using handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry.

Researchers analyzed 116 iron objects from sites spanning the 16th to 19th centuries, including early Spanish missions, battles, and settlements. The results showed consistent patterns in iron purity and trace element content across time periods, offering a new method to differentiate visually indistinguishable artifacts.

“A wrought-iron nail from the 1500s looks like a wrought iron nail from the 1600s,” said Charles Cobb, Lockwood Chair in Historical Archaeology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, in a press release.

Because the Spanish brought large quantities of iron – used in tools, weapons, and horseshoes – but changed manufacturing styles very little over time, archaeologists have struggled to assign artifacts to specific expeditions. This is especially true in cases where expeditions overlapped in both geography and chronology, such as those led by Hernando de Soto in the 1540s and Tristán de Luna two decades later.

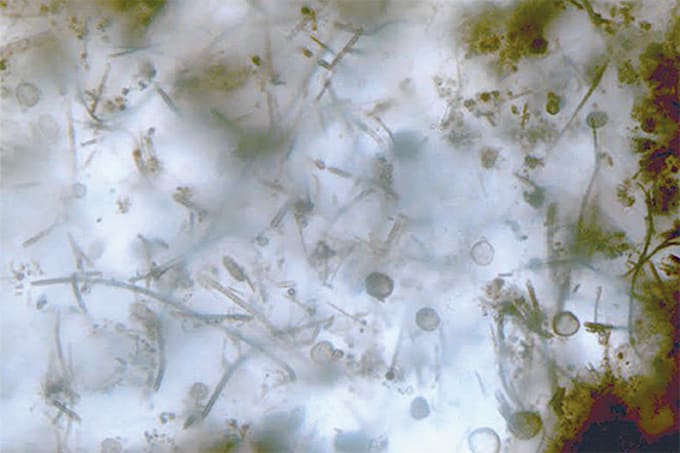

“Archaeologists find lots and lots of rusty nails and other rusty iron objects. We often can’t even tell what they are, so they get weighed, counted and put back in their bag. And usually, no one ever looks at them again,” said Lindsay Bloch, courtesy faculty member at the Florida Museum and principal investigator at Tempered Archaeological Services.

XRF enabled the team to non-destructively analyze trace elements such as manganese, titanium, vanadium, and bismuth – impurities that remain even after extensive forging and smelting. The results suggest that early colonial artifacts, especially from the mid-16th century, were typically higher in purity, while later materials carried a broader range of elemental signatures. Such patterns could help researchers better date and source ambiguous artifacts.

“She won’t brag on herself, but Lindsay literally wrote the manual on how archaeologists should use X-ray fluorescence spectrometry when she was a grad student,” Cobb added.

The study also builds on growing adoption of metal detectors in archaeological research – tools once viewed with suspicion due to their association with looting. “Metal detectors have a bad reputation in archaeology because they are often the go-to for people who loot historic sites,” said Bloch.

The team is now seeking funding for follow-up analysis using isotopic techniques, which could offer even more precise identification of ore sources and manufacturing origins.