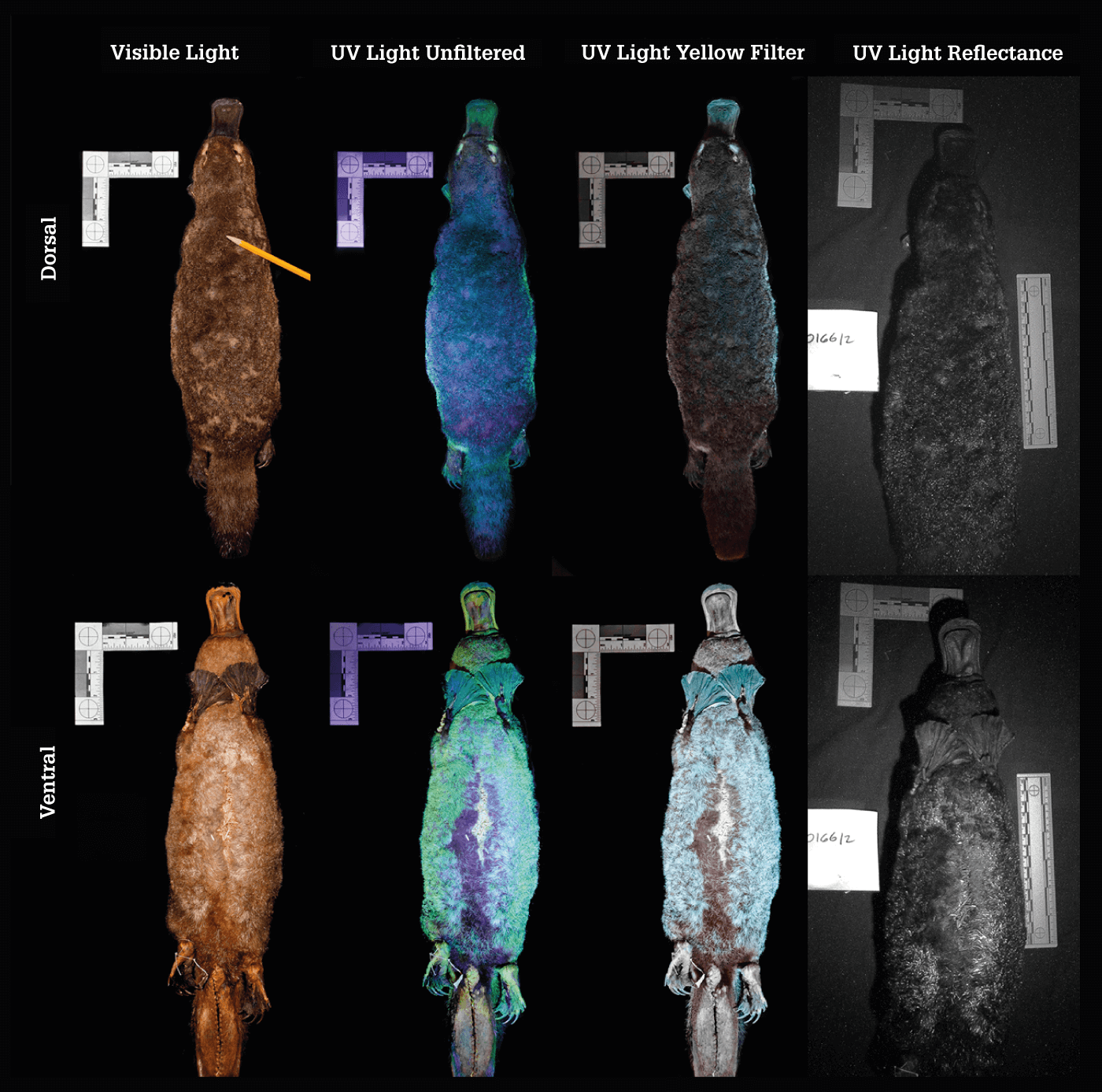

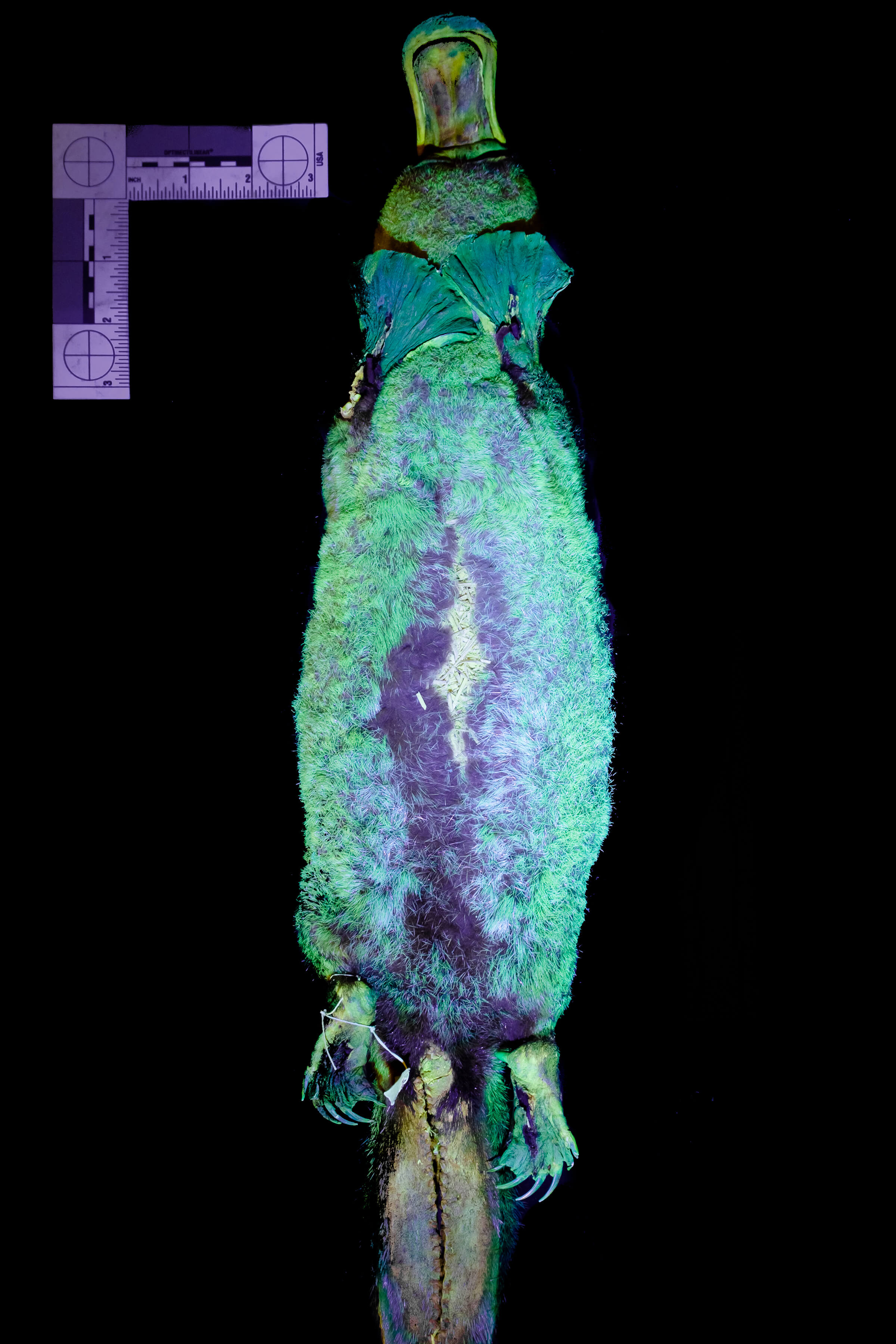

For the first time, researchers have reported evidence of biofluorescence in a monotreme (egg-laying) mammal under UV light – the eminently odd platypus. The team used fluorescence spectroscopy to analyze a museum specimen and determine which wavelengths of light were being absorbed and re-emitted. In the image above, cyan to green biofluorescence of around 500nm can be seen.

Biofluorescence in animals is an extraordinary trait that raises questions about species ecology and evolution. Up to this point, it has largely been observed in marine animals, but two mammals have also made it onto the list – opossums and flying squirrels. Now, researchers at Northland College, Wisconsin, USA, have reported the first evidence of biofluorescence in a monotreme (egg-laying) mammal under UV light – the eminently odd platypus (1).

“The idea that species may use wavelengths of light outside of the visible spectrum is fascinating to think about,” says Erik Olson, co-author of the paper. “It gives us a whole new perspective through which we can think about species ecology. Our discovery of this trait in an already well-known species that represents one of the most ancestral mammalian lineages highlights questions about the evolutionary history of biofluorescence, its biochemical basis, and its ecological function, if any.”

In the paper, the team suggests that biofluorescence may be important to species that live in low visible light environments – especially nocturnal-crepuscular ones. The trait could be useful in terms of interactions between platypuses, or even other species, such as predators. “However, we really don’t know,” says Olson. “There is a possibility that the trait has little or no ecological function. Only further research can tell.”

One of the big challenges for the team was the lack of specimens available for analysis: “We would have liked to document the trait in a living specimen, but there aren’t many opportunities to do that,” adds Olson. “Recently, though, a mycologist confirmed our observations of the trait on a wild, road-killed platypus in Australia. That kind of validation is good to have considering our relatively small sample size.”

The team certainly hopes to study biofluorescence in wild animals in the future. For Olson, the research is important for another key reason: “Our discovery has captured the attention of many – I think it creates a sense that the natural world is still full of mysteries to be explored. We are grateful our work has been able to highlight such a unique and awe-inspiring species.”

References

- P Spaeth Anich et al., Mammalia (2020). DOI: 10.1515/mammalia-2020-0027