Understanding how energy moves through semiconductors immediately after excitation is central to improving the performance and thermal management of electronic devices. Now, researchers at the University of Basel have directly tracked how energy flows from charge carriers into lattice vibrations in germanium, using a custom-built ultrafast spectroscopy setup that combines time-resolved Raman spectroscopy with transient reflection measurements.

The team showed that optical phonons in germanium heat up within a few picoseconds after excitation by 30-femtosecond laser pulses, before rapidly transferring energy to lower-energy acoustic phonons. The measurements provide a detailed, time-resolved picture of how electronic excitation is converted into heat – processes that ultimately limit switching speeds and efficiency in semiconductor devices.

“For the first time, a combination of two spectroscopic techniques allowed us to observe how energy is transferred step-by-step from the electronic system to the lattice. We can also observe how the frequency, intensity and duration of lattice vibrations change over time following excitation,” explained Grazia Raciti, first author of the study, in a press release.

When electrons in a semiconductor are excited by light or voltage, they rapidly redistribute energy among themselves and then pass it to the atomic lattice, generating collective vibrations known as phonons. These phonons govern how energy spreads through the material and how strongly it heats up. However, probing these processes requires both high temporal resolution and sensitivity to subtle lattice changes.

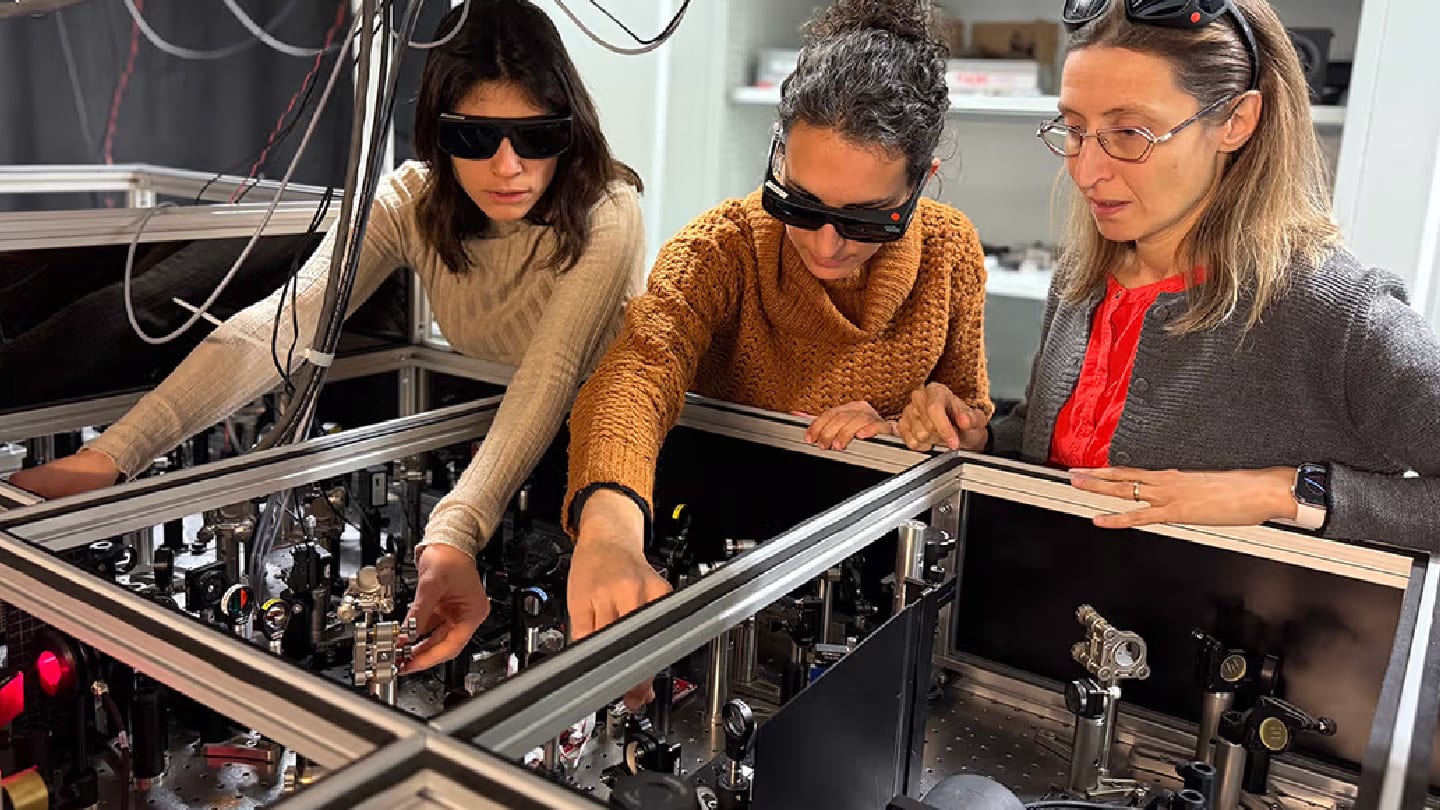

To meet this challenge, the Basel team developed a measurement platform that took three years to design and characterize. Time-resolved Raman spectroscopy was used to monitor small changes in the intensity, frequency and linewidth of the Raman-active optical phonon mode in germanium, while transient reflection spectroscopy tracked changes in the material’s optical response linked to carrier dynamics and strain.

The experiments followed the material’s response after excitation by ultrashort laser pulses delivered once per microsecond, with the relevant dynamics unfolding on picosecond timescales. “If we imagine that the time gap between two laser pulses (which is actually 1 microsecond) lasts 10 days, then the sample’s response that we record in the semiconductor lasts just a second,” said Begoña Abad Mayor, highlighting the extreme disparity between excitation and response times.

Despite these challenges, the researchers were able to detect changes of less than one percent in signal intensity and frequency shifts below 0.2 cm⁻¹, allowing them to distinguish between different energy-loss mechanisms.

The measurements reveal that, within the first few picoseconds after excitation, energy is transferred primarily from photoexcited holes to Raman-active optical phonons, raising their effective temperature. These hot optical phonons then cool on a timescale of around 2–3 picoseconds as they decay into acoustic phonons through anharmonic phonon-phonon interactions.

In parallel, transient reflection measurements uncovered oscillations in the reflected signal – known as Brillouin oscillations – caused by a coherent acoustic strain pulse propagating through the crystal. The damping of these oscillations was found to correlate with changes in the Raman linewidth, linking lattice strain to phonon lifetime effects.

To interpret the experimental observations, the team combined the spectroscopy data with density functional theory and molecular-dynamics simulations, enabling them to separate the roles of carrier-phonon coupling, anharmonic decay and strain relaxation in shaping the observed dynamics.

Germanium remains an important material for electronics, photonics and emerging quantum technologies, and is compatible with silicon-based platforms. According to the researchers, gaining quantitative insight into how energy is redistributed and dissipated after ultrafast excitation is essential for designing devices that heat up less, recover faster or respond more precisely to external stimuli.

“This basic research is vital in order to understand and further develop modern electronics and novel phononic components and may therefore lead to better chips, sensors or other electronic devices,” said team leader Ilaria Zardo.